We’d all love to think that the phone we carry in our pockets was a recent invention, but its roots can be traced all the way back to 1909. It was then that a little-known electrical whiz kid not only created the first device capable of sending voice wirelessly, but also the first radio station.

This story is not about Guglielmo Marconi and his telegraph or Craig McCaw and his cellphone empire. Rather, it’s a story about a high school dropout who developed an astonishing new wireless technology in Washington State.

Let’s step into the Wayback Machine and travel to 1909 Seattle. Against all odds, the city had pulled off the impossible – hosting the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the state’s first world’s fair.

We won’t bore you with all the details of the fair itself, except to say that if you ever visit the University of Washington campus, Drumheller Fountain (Frosh Pond) and the buildings that surround it sit on the original footprint of the AYP.

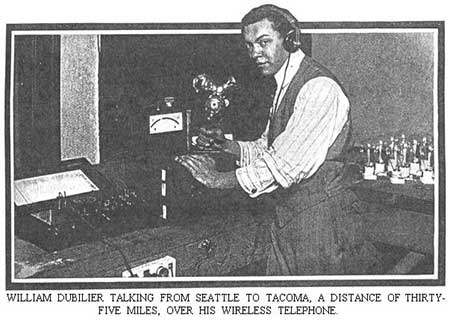

It was in one of these grand pavilions – the Manufacturers Hall – that William Dubilier set up his “wireless telephone.” True, there were other attempts to build such a device, but they were the size of a dining room table. Dubilier’s machine was just about a foot square in size, thanks to another invention of his, the capacitor.

While Marconi’s telegraph would transmit dots and dashes, Dubilier’s device could transmit a voice up to 35 miles away. “It is the greatest achievement of the age,” wrote the Exposition’s Director of Exhibits, Colonel H.E. Dosch. “I am mystified by its accomplishment… its future is practically unlimited.”

Dubilier himself predicted that one day “every car would have a portable wireless telephone to call for help in case of a breakdown.”

After the exposition, Dubilier put down roots in Seattle, determined to produce his new device for the masses. What he didn’t realize at the time was that his invention had other uses.

One day, while visiting Luna Park, Seattle’s version of Coney Island, Dubilier came upon a booth that charged 10¢ you could listen to voice and recorded music over a wireless. Dubilier came back time and time again to discover its secrets, only to find the booth closed. Then it dawned on him that they were broadcasting his own signals. He had created the first radio station.

In 1912 at Seattle’s Potlach celebration, he set up a booth so visitors could hear records play through earphones. Local newspapers went mad, calling him “a Wizard Youth” and “Seattle boy” and pronouncing that “Seattle May Be Made Famous By Astounding Success.”

Dubilier never found that success in Seattle. He couldn’t find the financial backing he needed to build a factory. Eventually, he made his way back to New York City, founding the Dubilier Condenser Company, whose capacitors fueled the rise of radio and then television.

Seattle’s rise to fame as a technological behemoth would have to wait until the latter part of the 20th Century. But William Dubilier, wherever he is, can smile down on Washington State, knowing that he changed the way we communicate and entertain ourselves long before there was a Craig McCaw or KJR’s Pat O’Day.