“The serenity of the climate, the innumerable pleasing landscapes, and the abundant fertility that unassisted nature puts forth, require only to be enriched by the industry of men with villages, mansions, cottages and other buildings, to render it the most lovely country that can be imagined.”

– Captain George Vancouver, 1792

A brief history of Washington’s economy.

One could start the story of Washington’s economy with more than 10,000 years of brisk trade and commerce among the indigenous people who inhabited these lands long before the first European settlers arrived.

One of the last “undiscovered” frontiers in the United States, Washington’s pioneer history didn’t really take off until the mid 1800s when President Fillmore offered land grants to any white male over 21. It didn’t seem to matter to the “other Washington” that native tribes were already living on this land. Initially, the new settlers were welcomed by the the indigenous inhabitants of the land. Chief Seattle was one of the region’s first entrepreneurs, pitching tents in Olympia near the custom’s house to welcome settlers, finding labor to work in area mills and taking visitors on tours of the area aboard his barge.

For better or worse, the floodgates had been opened to Western expansion, forever changing the face of what was then the Washington Territory.

When the transcontinental railroad arrived some 20 to 30 years later, industrialization and prosperity came at a breakneck pace. While it took the rest of the U.S. almost 50 years to embrace the Industrial Revolution, the transformation in the Washington Territory took a mere 20, leading one reporter to write, “Three years seem like a century in these days of fast living.”

The new frontier.

Being late to the party had its advantages, of course. Some East Coast cities struggled to accommodate new ideas brought on by the Industrial Revolution such as electricity and horseless carriages. But Washington’s cities accommodated them with relative ease. Any hurdles in civic planning came from the challenging geography, not the technological advances of the time.

The dense forests and rich coal reserves used to power the Industrial Revolution gave the state’s economy a boost virtually overnight. The Alaska Gold Rush added further fuel to the economic fire as gold fever swept down from the Yukon and into the increasingly crowded cities along the West Coast that supplied the miners.

Rapid growth did not come without a price. As lumberjacks, mill workers and miners tried to keep up with demand, workplace safety became a heated issue. In response, workers formed the first unions that guaranteed workers an eight-hour workday and worker’s compensation for job-related injuries.

Within one person’s lifetime, Washington had gone from an ancient Native American fishing and hunting ground to groundbreaking political and social experiments and an unrivaled period of innovation and invention, from the mighty dams that harnessed the raw power of the Columbia River to the taming of the atom to bring an end to a world war.

About Washington

A unique pioneer spirit.

It’s during this period that Washington’s unique pioneer spirit evolved. Early settlers had no choice but to fend for themselves and learn to live off the land. Shipments of goods from the eastern seaboard were at the mercy of fickle winds and unforgiving seas, taking months to arrive. Facing the uncertainty and inconvenience of daily life was not for everyone. It took grit and perseverance to turn adversity into opportunity and opportunity into progress.

The separation of cultures and ethnicities that was common in other parts of the U.S. was not as common in Washington towns. The rough and tumble existence of life in these parts required settlers to depend on one another to survive. The common ground became the work to be done and your neighbors were judged largely by their work ethic, not their ethnicity.

Men, women and children came from all walks of life to seek adventure and prosperity in Washington State. In the small coal town of Roslyn, a town of just 700 residents, 24 nationalities were represented in its one-room schoolhouse.

Men, women and children came from all walks of life to seek adventure and prosperity in Washington State. In the small coal town of Roslyn, a town of just 700 residents, 24 nationalities were represented in its one-room schoolhouse.

As with other parts of the country, Washington’s fortunes rose and fell with the nation’s economy. During World War I, the state’s shipyards turned out a quarter of all ships built during the war. When the Great Depression hit, residents stood in soup lines and lived in shantytowns. Oil replaced coal, closing many of the mines. Lumber continued to provide some stability, but it took a second world war to bring the region back to life.

During World War II, thousands of workers moved to Washington to build bombers, tanks and other weapons of war. At the war’s peak, Boeing’s Seattle plant turned out five B-17 bombers a day as everyone pitched in to win the war.

In the Cascade Mountains, lumberjacks felled giant, old-growth fir trees to mill into lumber for airplanes, ships

Post-war Washington.

After WW II ended, Washington’s economy managed to shift from wartime production to peacetime. Where the economies of Idaho and Oregon were tied to harvesting natural resources – which weren’t needed in such great quantities after the war – Washington’s economy benefitted from Cold War military contracts for new generations of aircraft and ships and the growing importance of strategically placed military bases.

Boeing led the way in this regard, so much so that one economist remarked, “As goes Boeing, so does the Puget Sound region.”

Even with Boeing as the region’s largest employer, Washington State hardly made a blip on the national scene. When someone mentioned Washington, the nation’s capital, not the state, most often came to mind. It wasn’t until civic planners secured a world’s fair in 1962 that the world began to take notice. Dozens of countries came to Seattle to exhibit at the Century 21 Exposition. The fair not only attracted an international audience but lots of media attention. The fair’s iconic Space Needle appeared in thousands of newspapers and on the covers of dozens of magazines around the globe. Even Elvis Presley stopped by to make a movie, It Happened at the World’s Fair.

From boom to bust.

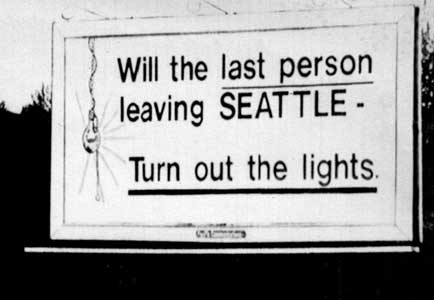

The glory days were not to last forever. In the 1970s, the U.S. government canceled its ambitious supersonic commercial jet project and the layoffs at Boeing followed soon after. With one out of five jobs tied to the aerospace giant, the economy tanked. Famously, one waggish resident purchased a billboard near the international airport that said, “Will the last person leaving SEATTLE – turn out the lights.”

The glory days were not to last forever. In the 1970s, the U.S. government canceled its ambitious supersonic commercial jet project and the layoffs at Boeing followed soon after. With one out of five jobs tied to the aerospace giant, the economy tanked. Famously, one waggish resident purchased a billboard near the international airport that said, “Will the last person leaving SEATTLE – turn out the lights.”

It was a hard lesson to learn indeed, leaning too heavily on a single economic engine. In the intervening years, the state became more diligent in its quest to create a more diversified economy, one founded on emerging technology sectors. Thanks to the aerospace industry, Washington had a higher percentage of engineers and technology workers than other states, who explored new ideas and created new enterprises. This included bold startups in the nascent information and communication technology industry, pioneers like McCaw Cellular, Aldus and Microsoft.

In Eastern Washington, traditional crops such as apples and cherries began to share the fertile land with grapes and hops. Sales of wine and beer made with premium Washington ingredients began to take off, as did new food manufacturing enterprises. Inexpensive power and plenty of water also gave rise to a new type of farm in Eastern Washington – the data farm – in communities that once relied solely on agriculture for economic growth.

A new direction.

Indeed, Washington continues to reinvent itself on multiple fronts as a modern economy based on innovation and creativity. Thanks to efforts to expand broadband connectivity statewide, rural communities are beginning to become havens for technology-based startups, from gaming and mobile apps to big data. Urban cores in major cities are enjoying a renaissance, attracting younger workers and families who enjoy the convenience of living and working in energetic downtowns.

Local business legends such as Amazon, Costco, Paccar, Nordstrom and Starbucks are being joined by other companies that want to leverage Washington’s pioneer spirit and reputation for amazing ideas, including Facebook, SpaceX, Twitter, Google and Apple.

As a result, exciting new opportunities are coming online. Commercial space, electric propulsion, medical devices, artificial intelligence, augmented and virtual reality and robotics are creating new jobs and new industries around the state, built with that same resilience, perseverance and pioneer spirit that has gained Washington its international reputation for innovation and invention.

A global pandemic that challenged economies around the world confirmed what state leaders knew all along; that diversification was the key to building resiliency into Washington’s economy. Even as certain sectors experienced downturns – tourism and aerospace among them – the state’s life science, agriculture and technology sectors continued to grow and mature, creating a pathway to rapid recovery and long-term prosperity as a vaccine found its way to market. As the world continues to recover from COVID-19, Washington is poised to enter a new age of prosperity and economic growth.

To that end, Washington’s industries continue to lead the way in innovation, blazing new trails in sustainable fuels, electrified aircraft and marine vessels, uncrewed and autonomous systems, space exploration, 5G, quantum computing, gene therapies, clean energy and more.

office hours

M-F: 8am – 5pm

Address

2001 Sixth Ave., Suite 2600, Seattle, WA 98121

Phone

(206) 256-6100